We also mention work created with designer Nadia Malik.

Andie = AS

My responses = PL

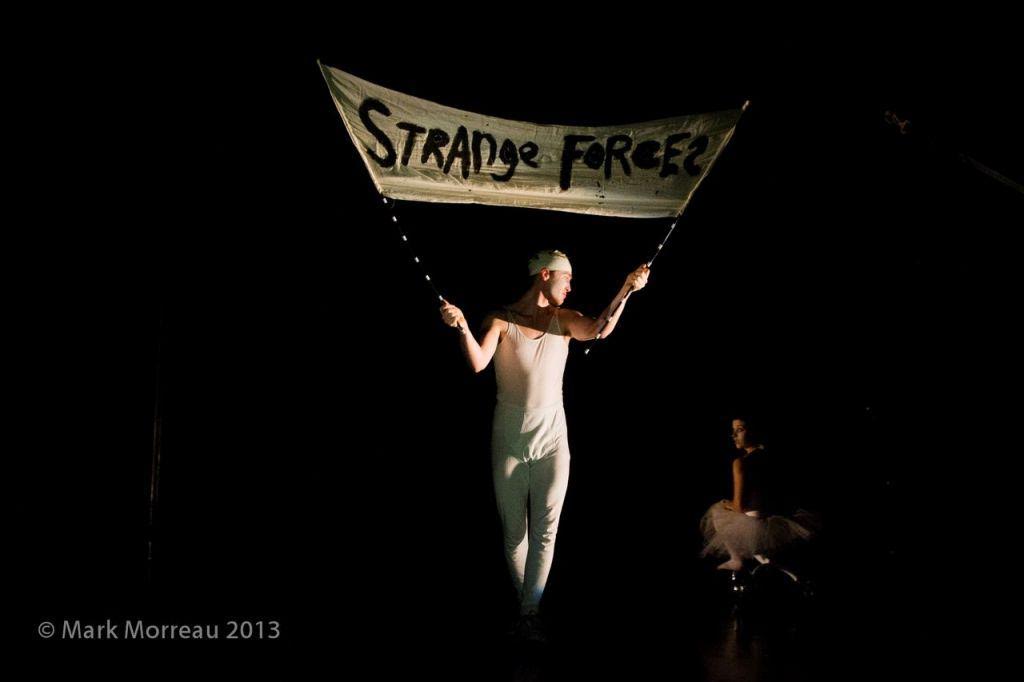

AS: In your direction for the linking pieces for Strange Forces at the National Centre for Circus Arts the rehearsal notes call for additional props each day. In what way do these props help you devise the performance?

PL: The props help define the world and they also help actions be more specific. For comedy, specificity is good – one of the prime comedic principles is clarity: when we know what is going on then we all can get the joke.

They are also the product of play or a playful state of mind. With the ensemble element of Strange Forces we were creating a fantasy world: Slave Clowns having to stage-manage the main acts of the show. It is a joy as a comedy practitioner to have polished, specifically made or chosen articles. In one scene a prop piece creates the illusion of a tiny man who is to be tortured by tickling. We needed a small red tickling brush. A longish handle as it is an implement for the normal-sized tormentor, and then a tiny tuft of red feathers at the end, to target the little man’s vulnerable spots.

If a talented performer is given a prop they might invent a further bit of business with it. This could be an extension of the original idea or simply an entertaining flourish. Good collaboration can expand possibilities, too. I wanted Pussy Riot masks in the show. The soundscape artist, when asked to source a Pussy Riot song said: ‘They can free the slaves!’ And so we created that scene of the liberation of the slave clowns.

AS: Often these props become costume elements and personify the characters. How do you visualise this to enable you to be specific about the props / costume required?

PL: In Strange Forces, again I think about the ‘little man’. The audience really identified and connected with this character. Here, I was using a prop piece used in vaudeville (a screen with a hole for a face and then and a manipulatable puppet body underneath), I’d also used this idea a few years back in a show about Brecht in Portugal, where we adapted the The Baden-Baden Lesson on Consent.

The safety goggles for the unicorn tamer were pragmatic in that they are given to NCCA students to wear when training with whips. This prop/costume piece reinforced the world the piece was set in (the pragmatic functionary garb worn by the ‘slave clowns’ - which in the main was white paper painting-and-decorating suits (which also summoned up chem-hazard resonances). In terms of the performer/character wearing the goggles, they reinforced both her lack of mastery and her vulnerability - the piece was about people being forced to do things that were dangerous. She looked simultaneously more vulnerable and more dangerous.

The numbers of the two characters playing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were puns for ‘spies’. The Hong Kong cast chose witty numbers for each character.

A lot of things I visualize come to me straight from the intuition. Other things I think – how can the idea be clarified here? What do the audience need to feel and understand? I talk and think this through with my collaborators.

There is a moment when two clown slaves shock each other using a prop which is basically a red emergency button. Andie made clown wigs out of coloured scourer pads. The jolly traditional clown look allowed audience to laugh more freely at their fear and reaction to the electric shocks.

One scene change in Strange Forces meant that the floor had to be wiped – to build the reality of the cringing clown slaves, I had them feverishly scrub the stage. A tussle over the wiping cloth ensued and one clown was reduced to using her own body as a dust cloth. Andie brought this idea to a fuller realisation by creating a ‘dress’ out of a length of dishcloth tube which that performer wore in this scene.

You can now see segments of Strange Forces on the Peta Lily Company YouTube Channel.

At the top of the show we created a drab and desperate little circus parade – we had our safety-goggle wearing lion tamer so one performer was ‘forced’ (in the reality of the slave clown world) to play the lion. This needed to be in the spirit of the ‘make-do’ and utilitarian look of the clowns and Andie created a mane for the lion using perhaps a dish mop sewn into an easy-to-put-on-and-take-off bonnet. Good costume construction means there can be more variety and changes in a piece.

Andie Scott also worked for me on a circus hybrid show Rhythm Town. The diversly skilled performers needed a world to marry their different performance styles and skills together. The company became a ‘travelling troupe’ in a retro-themed world (train travel rather than jet), employing suitcases and a steamer trunk with vintage travel labels. A basket ball was being used for percussive juggling and I requested it be painted like a globe. This both served the theme of the piece and harmonized with the world music used in the show. It turned a banal prop into something clever, that reinforced the detail and magic of the world. One section in the original show was an extended piece of music with a train rhythm – we introduced a bit more magic by changing the scale - introducing a toy train to travel across the tap table and performer’s bodies.

The props and costumes in this show allowed the show define a world alive so the performers could concentrate on their skills rather working as actors might to create the detail of the world of a play.

AS: In Strange Forces for NCCA we worked with very simple costume of white 'slave clown' attire using the cheapest possible materials: paper plates for ruffs, disposable overalls for clown suits, disposable shoe covers for hats and wigs... These costumes made the characters appear vulnerable and fragile. How do you convey these intentions to the performers during rehearsals?

PL: I inducted the performers to the Dark Clown genre I have been developing over the last 30 years. This work extends Red Nose Clown work into a darker palette, a darker spectrum of human existence and expression. The Red Nose Clown fails and suffers indignities and so does the Dark Clown – but on the darker side, the portrayal of suffering is cleverly designed to have an implicating effect on the audience. It aims at laughter flavoured with a cringe of culpability.

There was a strong start to the show where one clown drags on all the rest tied together in an aerial rope. One clown passes out before they are funny across the stage. This set up the game very clearly for both performers and audience – these slave clowns are being worked almost to the point of death. Carrying on regardless is imperative. (One of the inspirations for my Dark Clown work was Jane Fonda’s character in the film They Shoot Horses Don’t They? – set in the Great Depression where she continues to dance with her dead partner rather than lose her chance to stay in the Dance Marathon (even if she didn’t win, being in the competition ensured the character regular food as opposed to starvation).

The students learned the style and were supported in their portrayals as a troupe of slaves by the largely monochrome yet individual looks Andie developed for each of them in the show.

AS: In Chastity Belt and InVocation props become part of the costume, to be added to the body and removed according to the story. When the body is not present in those objects you use them as part of scenography. In what way do these objects change once they have been part of the narrative?

You can watch the trailer for InVocation on the Peta Lily Company YouTube Channel.

In Chastity Belt I use a hand-made prop (creating work on no funding): lemons on a piece of ribbon. These are at first a hag’s dugs, then become ersatz testicles, then Wonder Woman’s cape and lariat. My director Di Sherlock is very good at saying ‘use the such and such again in this moment’. It makes things more concrete and visually engaging and appealing for the audience.

The yellow marigold gloves are only used in the Lysistrata piece but are one of the splashes of yellow about the spare stage ‘set’. The lemon garland dresses the chair, then is worn in different ways to represent two different characters. When a piece is removed and discarded, it helps underline or highlight a transition point.

At a certain point the piece required a Kali necklace and I commissioned Andie to fabricate it – I would never have been able to make it. Andie ensured it was durable and good looking and that it resonated with the props I had already.

I suppose every western clown follows in that lineage. As women perhaps the journey is less straightforward. It is quite possible that some female clowns have been swallowed by history – performers like mime/dancer Trudi Schoop. There seem to be no female clown archetypes like the Auguste and the circus White Clown. The lineage is patchy. When I studied Commedia dell’ Arte, the main exploration was understandably with the mask work and little guidance was given for the female characters of Columbina and Harlequina. I seens to be that female performers such as like Lucille Ball and Phyliss Diller used a kind of clown in sit-com and standup formats.

Interesting to observe that some female clown performers often dress in male attire: Angela de Castro, Nola Rae, Guiletta Masina in Fellini’s La Strada. When I started the company Three Women together with Claudia Prietzel and Tessa Schneideman in 1980, I was inspired to create a style of mime that was not presenting the archetypal ‘everyman’ but which instead showed the pain and ridiculousness of aspects of being female. We had a piece about putting on makeup, a piece about women and their handbags and what was inside them, and we created a clown-like circus using solely household items e.g. an old-fashioned handle-operated eggbeater became a unicycle, a rolling pin was weight-lifted by a strong(wo)man and an old fashioned hairdryer with hood was used as a mask to create an elephant and so on.

I started to teach clown decades ago because a female theatre company begged me to teach them. They said they wanted to know how women could become clowns. I remember at this time, people actually had conversations about whether or not women could be funny.

I teach and direct in the Dark Clown genre but have not performed in this style – yet. I hope one day to create a piece where I do that. Someone once described Chastity Belt to me as ‘dark’ clowning but for me it is not in the style that I teach and direct as Dark Clown. There are serious points made in the show (moments of bite but with the humour going on around it) – and perhaps that is what that person meant.

When I created my show Topless – about breast cancer, lost love and ‘getting things off your chest’ I thought it would only appeal to female audiences, but in the creation of each beat, I had my eye on what would be entertaining, and a strong instinct to avoid sentimentality or self-indulgence. I wanted the show to be funny and entertaining. I knew it needed to capture the attention at the beginning, have a sense of suspense about the outcome and a good finish. When I was small my parents went frequently to vaudeville and the pleasure of those early experiences of silliness and sexiness and a little bit of scariness and skill all performed live must have left a deep impression.

AS: Within these themes of loving, fragility and the survivor how does the costume identify your stage personas in Chastity Belt and InVocation for example?

PL: From 2002- 2008 I did not perform at all. I made InVocation between 2008 and 2010 and with Chastity Belt it was all still quite new.

In the early days when my work was funded I had an aesthetic to have as few props and costumes as possible. Then when I was returning to the field, I was creating work unfunded.

As in the early days, a new project always needs to have a photographic image to promote it – often created before the funding is secured. I asked a designer friend if she might be able to loan me a corset for a photo shoot. I thought I would wear a corset and wear boxing gloves. My friend (designer Nadia Malik) could provide no corset but there were two tutus. A red one and a white one and they served very well. It was only on the last outing of the piece that I realized these colours served the passion that was being farewell-ed and the pristine alternative (the silvery autonomous Goddess Diana) that was being embraced.

I always thought the tutus were glamorous. My director Di pointed out to me one day that they were clown-like! So there you go – as a mature performer, if you can’t afford glamour, then the clown will serve you well. A bit of tat = the equivalent of Chaplin’s tramp costume?

InVocation as a piece had a long gestation. In the creation of the piece I was healing the difficulties of events of the non-performing years…it turned out one of the themes was that of identity. The same theme that pervaded Topless I discovered, only towards the end of creating the piece and realized in fact through the creation of the piece: how do I live now I am divorced, now that I am older? With InVocation I wore rehearsal gear, yoga gear and a business suit (and of course, the breast plate). Nadia Malik had ghostly see-through plastic torsos hanging as part of the set.

In the recent remount of InVocation, Andie realized certain new elements to the set and costumes. In the end I strip out of the business suit and what in heck was I going to wear? It was a struggle bravely faced and satisfactorily solved by Andie. What undergarments will suit the older body, not be too revealing, not too unitard-like, not be too sexy, not too unsexy, not too sad-sack looking, not too period-specific. At the end I needed to don the breast plate again - Di wanted me to perform a speech from my play The Porter’s Daughter to highlight my decision to leave business coaching and return to theatre.

AS: In your performance of Crystal Lil (costume conceived, designed and made by Nadia Malik; piece directed Anton Mirto as part of the LCF MA Costume and Performance degree course show produced by Donatella Barbieri), the costume becomes an inhabited sculpture. Can you describe how this performance differs from your own work, for example did you feel restricted working within someone else's direction or was this liberating?

It was a great process. Director Anton Mirto made a wonderful piece and got a very different performance out of me. She also accepted my moments of collaboration during the process. And both Anton and I were both serving to realize Nadia’s concept and the story she had chosen. The costume needed to be managed well to make the most out of each moment for the character and to clarify what the character was doing. In my 1988 show Wendy Darling I had a plethora of props and before each performance would rehearse carefully each moment of prop manipulation. It’s a skill and a discipline to make your props look magical.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed