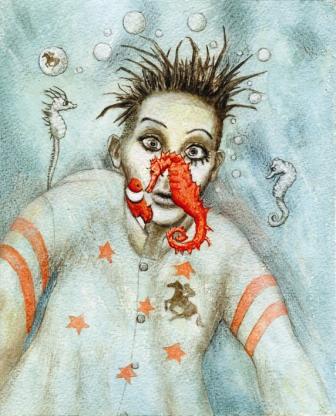

photo: Tiff Wear

photo: Tiff Wear This article contains learnings from a variety of sources which I have used and tested melded together over years of performing and teaching Clown and comedy. I am not a stand up comedian – for that medium, I refer you to the books of Oliver Double and Jay Sankey. (Getting the Joke Oliver Double Zen and the Art of Stand-Up Comedy by Jay Sankey)

The audiences I refer to are small theatre audiences rather than street theatre, although many principles and practices here can be transferred to either standup or street performance. Most of my teaching is geared towards no-fourth-wall performance, though I have found, once these lessons are learnt, they can provide actors with added sensitivity and awareness which can have positive benefits on performances in fourth-wall pieces and plays.

In 1984, I studied with Gaulier, at his first ever course in London. Gaulier taught via short anecdotes and extremely practical tips and instructions. I was thrilled to apply these to the show I was already touring and found that I could create more laughter, more reliably. In my clown teaching I shared this knowledge. It was thrilling to find that laughter creation could (to a degree) be demystified. And through continued practice and observation, I built up a store of techniques.

I will refer to clown teaching mainly, and this article concerns itself with craft rather than content.

A disclaimer: There are no guarantees with comedy. Comedy is subjective.

But in my experience, over many years, I have seen that these bits of craft can give some useful grip holds.

Chapters

1. get with your audience

2. respect rhythm

3. accept everything

(4. never underestimate your power to affect the audience – coming later)

● ● ●

Chapter 1

Get with your audience

Getting with your audience (step one: getting their attention) is easier in theatre than in street performance where the performer must carefully choose and mark out the ‘pitch’ and attract their audience by speech - either declamatory or low key chat - or by laying out props or equipment or by some other intriguing action or even intriguing stillness. Clever street performers learn to structure their act strategically so that the crowd is compelled to see what will actually happen.

In theatre, unless it’s an immersive performance, the audience is tidily seated together in chairs facing the performance area. It’s good to look after the configuration of the auditorium, where you have a choice about it. Not too big a gap between stage/performance area and seats. Not too wide a central aisle, if there is one*. It’s really useful to think about the space in terms of chi (using and adapting the principles of chi gung or feng shui). Where and how is the energy flowing?

Are the audience sufficiently compacted? If you have a thin house then remove chairs if seating is flexible, or ask the ushers to shepherd people into the front rows. Gaps between audience members does not help laughter take hold or grow. Think of audience members like logs and laughter like a flame. You need the right amount of togetherness to create the natural phenomenon of contagion. Laughter is social (see Provine’s book Laughter: A Scientific Investigation by Robert R. Provine). You need to energetically make your audience feel themselves as a whole. This is why comedians often say: ‘Good evening Hammersmith (or wherever)’. They are creating communality in the here and in the now. They are also setting up the call and response rhythm. More on that later.

So you have your audience seated in front of you. But that shouldn’t be taken for granted. We have all seen unenchanting performances. And then there are those performances where we are drawn in, where we feel magnetically connected to the performer/s.

What can the performer do to increase the likelihood of being in the second category? How to understand and make the best connect with an audience?

Before you can get with the audience you need to get with yourself. Be in your body with a relaxed, alert, elastic energy. Be present. When I welcome people to a course I do a number of things to help make these things happen, to create the conditions to keep judgment to the minimum, freedom to play in ready supply and a ready, soft, flexible focus available. There will be another article at some point on how I create the conditions for play and learning on a course. In this article we’ll stay focused on the relationship between the performer and the audience.

When you look remember to see

When people get excited or anxious, the muscles of the eyes tense (tunnel vision) and it’s easy to miss opportunities. We’ve all stared out at our audiences without seeing a thing. Performer, storyteller and novelist Danny Scheinmann calls this kind of eye contact ’spraying’ and humourously likens it to ‘pissing on’ people. He says ‘it feel nice and warm to begin with but it soon grows cold.’

One of the first exercises I teach on my Clown workshops begins with giving people the instruction (and thereby also the permission) to look into each other’s eyes. ‘No particular way you need to be. If a smile comes, great, if a smile goes, great. Whatever happens is fine.’ The relaxation in the room is palpable. I give this instruction: ‘When you look, remember to see.’ In my experience, in the situations I teach, this not only helps people relax, it is a preparation for really seeing their fellow performers and the audience.

‘When you look remember to see’ is knowlngly phrased as a joke. It’s aim, though is about the quality of seeing, a kind of seeing where attention is being paid.

The audience’s reactions – no matter how subtle - are information for the comedy performer (and any other performer for that matter). I work to get people to do a lot of direct seeing. Once this is truly learnt, later one can transfer the awareness of the audience to peripheral vision and ‘feeling with the pores of the skin’. This is useful for fourth-wall and non comedy applications also.

Where does a laugh start?

Gaulier used to ask: where does a laugh start? There are all sorts of good answers to this: in the brain, in the stomach, etc. Gaulier suggested it was ‘in the eyes’. Switching our attention from ourselves to where it counts - to the audience/other. We all know that fake smile we put on when Uncle Eric/Auntie Elsie is coming for lunch. The mouth hurts with the effort of stretching but the eyes are dead. When we are genuinely happy or charmed or interested, the eyes are lively, moist, lit from within, moving softly and responsively. So charm first. And erm, no, ‘charm’ is not achieved by stressing the audience out with your ‘like me' face (we’ve all been there!), but by simply putting your attention on them.

Get the eyes ‘smiling’, then it’s your next project to see if you can move that down to the mouth corners (Gaulier would say), then see if you can move that down into their chest, to adjust their breathing (more on this later, in chapter 2) and then you are in a good situation to be able to release a laugh.

Of course, having practiced ‘looking to see’ the course participant often needs many reminders to soften the eyes to combat the tension of fear and/or excitement that can overtake them in any moment. When I teach clown work, the participants are in a state of constant improvisation. Creating something from nothing, or almost nothing.

It’s the clown’s job or genius to be able to mutually invent with their audience a new world of possibility arising out of the moment. It’s an act of communion.

The clown creates a world in the empty space, rather than entering into a world that already exists.

Avner the Eccentric’s Eccentric Principles #10

And ideally to also make people laugh.*

‘Useful working definition of a clown: A clown is someone paid to make people laugh.’

Philippe Gaulier

*(while taking good note of Avner’s Eccentric Principle #17)

Of course ‘make ‘em laugh’ is a terrifying instruction**. Sometimes even for the not-so-beginner.

Adjust your attitude

Now for a moment, let’s take a step back (or to the side, or somewhere) and talk about something largely unconscious: attitude. Getting with the audience means having a ‘with’ attitude.

It’s usefully reductive to think of humans having two prime motivators: fear and love. Fear makes the audience an adversary. The 'against' or 'in spite of' attitudes. The aikido master knows the value of the 'with' energy. It’s the ‘Ai’ in Aikido, which means joining, unifying, combining (the Aikido master I know says it means ‘love'. It commands the most effortless use of energy and the strongest results. (**Yes, there’s a way to deal with fear but I don’t have space to cover that here.)

So about this ‘with’. Here’s one helpful practice (after which I will share with you an invaluable technique). I spent a period of time practicing chi gung every day - there's an exercise where you face a tree and drink in energy from it via the soles of your feet, draw it up through your body then circulate it back to the tree through the crown of your head. I started to think about this action when I faced audiences. Everyone knows a good audience gives you extra energy and extra play. But even a quiet audience is giving you their presence. And in terms of chi that's a lot. This is a great way to cultivate a flow between you and the audience, and to install the ‘with’ attitude versus the dynamics created by the often unconscious ‘against’ or ‘in spite of’ attitudes where the audience is perceived as something to defend oneself against, or something to deny the presence of, or try to impress or gain the approval of, or even something to attempt to conquer.

I mentioned earlier the very valuable principle: Make your audience a whole. Now here’s the best exercise I ever learnt to make the audience a whole and it simultaneously serves the function of providing that crucial ‘with’ attitude.

Cast a net

This technique was taught to me by Alison Skilbeck. She calls it ‘casting a net’. It’s best to be learnt physically. One casts an imaginary net in the manner of a fisherman who works with hand-cast nets. Pick up, throw, let go (soft arms and hands), let the net hover for a moment above the other person’s head … then idly wait for it to fall (or watch it fall, using your soft, peripheral vision). Once you’ve got this, you eliminate the arm actions of picking up and casting the net.

People watching a version A (no net) and version B (invisibly cast net) report a multiplicity of differences. ‘Casting the net’ tends to slow the performer (the net caster), to make them more present, more responsive to their audience, more relaxed, more aware of the flow between them and their audience and can even make the caster’s voice better modulated and more resonant. PLUS it visibly creates more engagement between caster and castee. The castee almost always reports that version B is the one where they really want to hear the rest of the story.

Here are the steps for learning to ‘Cast the Net’:

- Face your partner, be around 8-9 feet apart.

- First simply walk up to them (5-7 feet apart) and say, ‘Hello X, I am going to tell you the story of The Three Bears.’

- Return to your start point and approach, stopping to pickup and with your (soft) arms, cast the net as described above. Let it hover, allow time for the net to fall. Have you attention gently on the other while the net falls. Repeat the same sentence ‘Hello X etc’.

- Get coaching from your partner (hands too close, arms too stiff, net thrown away, net thrown in face, net too tight etc). If necessary repeat till the result of engagement is sensed.

- Then do it with your imagination, i.e. no hands!

Applications of casting the net

This technique uses the natural function of focusing our human awareness – we have all felt having our audience, or a group of friends in the palm of our hands. Now this way of focusing our attention (normally spontaneous and unconscious) has a name and it can be used on demand.

I have discovered a number of applications for the technique.

Try with a group of four or five. Outside observers often report seeing the effect and those netted can sometimes sense it. Consciously or unconsciously, the audience begins to feel itself as a whole.

This technique can be used to 'harvest in' latecomers in a meeting or workshop situation.

It can be used to give special focus to a single person in the audience and – most importantly - it can be used to make the audience whole again after the individual interaction. Once one has the hang of it you can cast a net over an individual audience member and engage with them - while simultaneously casting one over the rest of the audience to ‘keep them warm’.

There is no limit to the number of times you can cast a net. Contact with the audience is not something achieved once. It is a constant practice that needs ongoing calibration and renewing.

I have worked with some people who have a bias to favour focusing on one side. (Perhaps they have an eyesight, postural or habit issue). In this way people can be neglecting a third to a half of their audience. Laughter is contagious. Not laughing can also be contagious. If you are excluding a third of your audience, beware. It won’t happen immediately, but after a while, that third will influence people near them, like a stain spreading, and soon you are working with a much smaller field. Lost laughter opportunities cannot be regained. The audience may still laugh through to the end but the laughter will never swell and expand to the level it would have done if the whole audience were included.

I combined ‘casting the net’ with the ‘rule of three’ to create an exercise where much hilarity can be created using only the text ‘Good evening’.

Any audience can be divided in to three parts: those to the right, to the left and those in the middle. The exercise trains the clown to make something out of nothing. This sentence – itself containing a delightful 3 syllables - can be played to: whole (always start with making your audience a whole) then side, side, middle, whole again. Side, middle, other side, whole, and back again. Whole. Then you can deliver a syllable to each section: 'Good. Eve. Ning. Eve. Ning. Good.' Then accelerate by quickly and randomly doing rapid individual ‘Good evenings’ to everyone in no particular order.’ Playing in the style of clown, be sure to have an amusing sound in your voice (even if that be deadpan) and have the skill to repeat exactly what needs to be repeated (gesture and words the same as they were when the audience laughed) and to have the sensitivity to know when to start a new ‘chapter’ by changing the tone or rhythm to provide variation or make contrast or layer up what you are doing to grow the response.

IN a traditional theatre venue you can apply this to stalls, dress and balcony. Perhaps alternating the horizontal partition with the vertical. One day when I play a West End theatre I’ll report on how it went.

You can cast a net over your fellow performer (a great way to get ‘with’ your fellow clown. Add this into working with Major and Minor (Major and Minor is not about status, but about whose turn it is to play – see Philippe Gaulier’s Le Jeu Workshop) and you can ramp up each other’s charisma and energy. Take all this for your own testing of course – casting the net does work but there are so many variables involved that one cannot guarantee an exact outcome of trying to apply an exercise learnt from the page.

You can cast the net sideways as you enter, in profile.

You can also cast the net over yourself – it’s calming and centering.

You can cast the net in your imagination from your dressing room. Cast it again form the wings and when facing front.

Other attitude transformers:

Moving away from ‘casting the net’ now, here are two more useful attitude-changing principles from Philippe Gaulier.

Do we ever take the time to think what our attitude is towards the audience? It’s usually something that happens non-verbally, unconsciously. In a nervous moment, one might look out at the audience as if they were a convention of Grim Reapers. Or perhaps you unknowingly brace yourself as if the audience contained those children who told us we smelt in grade two, the teacher who hated us in high school, that parent who humiliated us etc.

Far better to think of the audience as:

a/ Baby in a pram (or, to update: stroller or car seat)

When it comes to clowning, much laughter can be produced from the simplest (or seemingly simple) thing. Clowning is not intellectual. Often we are laughing at the conjunction of a shape and a rhythm (see chapter 2 below). So think of leaning in towards a baby. First we look at the baby - picking up non-verbal information about its state. ‘Ahhh boo boo boo boo,’ we might say. And if we get a reaction (or in order to coax a reaction we repeat, ‘Ahhh boo boo boo boo!’ and because there is something in our human DNA or psyche that loves the rule of three, we’ll do it again. ‘Ahhh boo boo boo boo.’ We make these sounds for the baby’s pleasure and our own. And unless we hate babies we’ll continue beyond three, into another set of three, perhaps. But at the first sign of baby’s mouth making a down turn we abandon the sound that we were so proud of, and try something, any thing else: ‘Breeee! Breee! Breeee!’

The whole audience needs to be the baby’s face, not in a generalised way, you need to really see them and make a careful (quick, intuitive) assessment of the whole in each moment.

Always be ready to abandon a game.

The only failure you can have is the failure to aCknowledge the failure.

Any failure might be turned around by allowing the audience to know that you have seen how they are feeling. The moment of failure gives a chance for the Clown to show their humanity - a chance for the comic to utilise the useful principle of ‘comedy = truth + pain.’ And then to do something – anything – to ‘make them forget about it’ (Gaulier).

I use the baby-in-stroller to also demonstrate the game of show and withhold. ‘LookaddaPanda!’ (hide Panda) ‘LookaddaPanda!’ etc. This concept also illustrates the game of tension and release which is a prime ingedient of comedy. I use the age-old game of 'peep-oh' (peek-a-boo) as a pair exercise (one doer, one witness) to help students practice playing with an elastic suspense, and to practice the principle ABC. (In sales this is Always Be Closing the deal). In Clown it is Always be Calibrating. How did they look sound before I did the thing, how do they look now that I have done the thing? And ideally, how did they look during? How do I feel about it? What might they need now?

b/ Audience as a cooker top

Imagine the audience is a large cooker top. Each person is a different pot or vessel with its own ecology and needs. There are some peas boiling on high over there you need to keep a close eye on them. There’s a casserole on a steady simmer. A double boiler that is slowly melting some chocolate, a steak that needs flash frying, something that needs a slow stir, or shifting onto a lower flame … each part of the audience needs attention and each moment is a new moment.

About call and response (and the habit of laughing)

‘This is the first time you’ve worked together as an audience.’

Leonard Cohen

If you are working with text and wish to encourage your audience to vocalise, then it’s helpful to think of a question to which there is going to be an unanimous response (or as close to unanimous as your can get). Or to cover a number of questions to tease out the different quarters of your audience.

Best not to be a hypocrite – if their response was disappointing you can’t gloss over it. The audience need to know the interaction between you and them is real and happening in the here and now. Of course there may be a situation where you know it’s not going to get any better than that - so, for the sake of timing you might move on to avoid a lull in pace and move towards something in your piece that is sure fire, or that you hope is going to do the trick. ABC.

Whenever you are scripting some audience interplay, frame your questions accurately and strategically. Imagine the possible responses to any questions you ask and script funny cappers for each possible response. Of course some occasions one must rely on your improvisations in the moment.

Comedians speak about getting the audience in the habit of laughing …

We have already partially moved into the next mini chapter here. (In practice, of course, all the principles overlap and work together).

Chapter 2

Respect rhythm

Ok, here comes one of my favourite sentences of all time.

When I was in a workshop led by Carlo Boso, Commedia dell’Arte expert, he said:

‘It’s easy to make an audience laugh. All you need to do is to control their breathing and their heart rate.’

‘It’s easy to make an audience laugh. All you need to do is to control their breathing and their heart rate.’

Carlo Boso

This thrilled me when I first heard it. "Great there is a way!' I thought. Then: 'But how?!' My mind visualised a theatre whose red velvet seats were occupied by audience members strapped in and covered in wires and electrodes and respiratory devices. Of course there are no electrodes in theatre auditoriums – yet – so what can the performer use? The performer can use their resources or their own good self. What does the heart rate and breath have in common? They both physiological, both rhythmic.

Now I prefer to adjust Boso's principle to 'affect' the audience (just because it sounds less controlling).

It was once explained to me that the underlying rhythm of Comedy was the rhythm of a happy heart beat. The rhythm of Tragedy meanwhile is characterised as a dying, decelerating heartbeat.

Comedy is regenerative. At the end of even a troubled comedy such as, in today’s thinking, 'The Taming of the Shrew’, there is a banquet and a marriage. There is food, there may well be children, life will go on. The sense of an unstoppable heartbeat. This resonates nicely with the unkill-ability of the cartoon character. Nothing can kill Wyle E Coyote. He re-inflates and reconstitutes after every steamrollering, cliff top fall or explosion. A killed Commedia character will have limbs which refuse to assume the horizontal.

Predispose your audience to laughter

If you are going to work with rhythm, set your base rhythm, your underpinning rhythm. Choose a good ‘happy heartbeat rhythm’.

Once I was standing in a cafe lunch queue with a friend who was telling me about the death of a friend. Abba was playing on the sound system. After a bit our conversational rhythm of ‘oh, ah, oh dear’ petered out - there was a hiatus and we started subtly jigging. We could not maintain the sad tenor of our conversation. It’s not that Abba was our favorite band. It was the rhythm we could not resist.

The happy heartbeat is the base line - we need all the rhythms to play comedy. Audiences need variety and even moment is a fresh moment.

If good rhythms are clearly and appropriately installed, the audience* is stimulated to copy or embody those rhythms. Even if subtly. In the old fashioned travelling circuses, the music playing as the crowd marched into the tent would not be Mahler or Stravinsky. It would be, most probably, a march (think of the classic circus marches e.g. March of the Gladiators) or a merry tune or a waltz perhaps.

(*Although I did once perform before an audience who thought it good theatre behaviour to assume the verisimilitude of seated death. We did warm them up but it was tough going. I learned a lot that day watching my co-performer. ‘What do you do when they are like that?’ I asked. ‘Love them,’ she said.)

On a clown course, I like to teach a little clown run, even before I teach clown state, to show the audience how effective rhythm can be.

I have come to think more and more about the physical act of laughter. Think of ‘priming’ your audience’s ‘laughing gear’ i.e. the heart and the lungs (and the muscle of the diagphragm!)

I believe it’s useful to master being in command of your own rhythms.

Basic clown exercises to develop and show the power of rhythm and contrast

Master traversing the stage with a single good rhythm (keeping good contact with the audience all the while).

Run three times across the stage. Learn to sense when to go immediately and when to tease out the audience’s desire to see it again. Know that the turn at either end (if visible) is an interruption, and a contrast -the sorbet between courses, salt and lemon to the shot of tequila, cream between the Victoria Sponge layers. (See further below: ‘selling two things’).

Now run across and simply install a different rhythm contrast (at exactly the half way mark – there is meticulousness and precision in clown work to heighten and hold in place the anarchy). Aim to master this change with no acceleration, no deceleration, no pause, no intervening step, no telegraphing, no event, no meaning and no comment.

Master a succinct little trip. Arrange for it to happen precisely on centre stage. With a good rhythm either side, the ‘laughing gear’ is primed, the trip is an interrupt, and can release the breath in a laugh, the eyes having been prepared – see chapter 1. Other things need to be in place to get the result in this clown exercise: a good fixed point (so that the performer is visible); a clear, good rhythm; good elastic energy; good contact with the audience.

Laughter is cumulative

I got a very clear picture of how graphic this can be during a run of a show I used to perform many years ago. I had gotten used to the structure of the show producing a laughter pattern. One night I fluffed a word so the rhythm and emphasis wasn’t optimal and the sense was less clear. I still got a laugh on that line but not as much as usual, and the subsequent four laughs and the payoff laugh was far less amplified than it should have been. If you can imagine a graph with time on the base axis and amount of laughter on the vertical axis, then see a graph line running and peaking at the response to the scripted joke lines and laid one evening over another, you would see lines part company and the spikes on the night of the fluffed line much reduced.

Laughter is physiological

Like any physiological process, laughter has phrases, plateaus, peaks, troughs. Hard laughter can be tiring. Sometimes you may need to soothe and calm the whole or part of an audience down. (Think of the Clown who puts a finger before her lips: ‘Shhh!’ or the comedian who says, ‘No but seriously now, seriously now - my Grandad had his birthday the other day.’ Audience: 'Ahhh'. ‘He’s 86.’ Audience: 'Ahhh'. Bit more set up then … unexpected unsentimental comment (surprise punch). Audience: big laugh all together on cue.

Repetition and Rule of Three

‘If it was funny once, it should be funny again’

Philippe Gaulier

For the standup, the repetition of the ‘call and response’ rhythm is key. Comedians also use the rule of three. From Fairy tale to MLK, I don’t think there is much use denying the value of observing the Rule of Three.

In Clown work I recommend students really use the rule of three. Of course it must be used in conjunction with the other variables such as suspense, sensitivity, flexible energy, contact and joy.

In a class situation it’s a safe place to over-ride the English resistance to /fear of ‘milking it’. Unexpected bonus is that - if there is failure, you get to practice dealing with that (see chapter 3).

Gaulier used to say ‘The rule of three and then the fourth with a variation.’ Build the pattern then embroider on #4.

I like to encourage clowns to build the repetitions as much as they can – always being sure that you are delivering the same thing (developing proprioception of voice and body is key here), not ignoring other valuable nuggets such as ‘don’t sell too cheap’, also sensing for the right moment – When do they want it? Do I give it then or make them wait (even if that wait is a nanosecond long). Are they ready for it, do they deserve it? Are the conditions right for them to receive it? Are they expecting it? The clown (or clown performer) should ask themselves lots of questions, Gaulier said.

Selling two things

Sometimes when selling a repeated thing, an interruption happens (e.g. someone in the audience makes the clown feel a certain way, and that something is amusing to the audience, or the clown feels frustration and that expression of frustration*** is amusing to the audience).

*** useful to think of ‘the thing’ as a combination of shape and sound. Or sound and rhythm. Or Shape and rhythm (as opposed to an idea).

With two things to sell, you can alternate them. This done (with skill, stamina and awareness), can raise the energy in the audience. And compound the laughter. It’s called ‘snowballing’ the laugh. ‘Snowballing’ may be done simply by acceleration of one ‘thing’. Or you mix acceleration with two ‘things’.

Then ‘just before the audience becomes bored’ (Gaulier). Or just before they become tired, you ‘surf the wave of laughter’ into something else.

You can always do a call-back to the golden ‘thing’ later if that feels right.

What I mean by Calibration

I said earlier ABC. Always be calibrating. Calibration is the antidote to Hypocrisy. And it’s a usefully less charged concept than ‘being truthful’.

There is a clown exercise where the clown is selling its enthusiasm, growing the muscle to reproduce the same ‘thing’ and to notice who laughs. Sell it specifically to the first laugher again. Notice if a second person laughs, sell it to that person … sell to all the laughers … notice those not laughing yet. Think to yourself ‘They may be Belgian’*****(Gaulier) and make the thing clearer.

Instead of 'sell' you can think 'share'.

****** Apologies. Belgians, I love you and find you have a superb sense of humour. This was Gaulier’s way of saying ‘people with impaired sense of humour, need a little help to really get the joke.’ It counteracts the negative brain talk that goes: ‘those people don’t like me I’ll ignore them’.

You need to notice any dip in the quality of the laughter and respond accordingly – e.g. ‘what happened there?’ ‘Hm, let me test to see’.

Notice how people are before the thing, then after the thing. Measure your own feelings about that and be specific e.g. thrilled they like it, or inconvenienced at being interrupted, or still pleased but curious when it’s a tad less than the previous time ... etc, etc.

After a big previous success, you might also go to a flamboyant expression of ‘I’ve failed! my ‘thing’ is broken’ (secretly be optimistic though, and turn upstage to fervently rehearse the ‘thing’ before re-presenting) or ‘what is wrong with these people?’ (secretly you adore them).

As you can see the possibilities are endless.

So again: ABC – always be calibrating.

Notice how people are before the thing, then after the thing. Measure their reaction. Repeat the thing to test it. Test again to be sure. Each time measure the amount and volume (even, with experience, the rhythm) of the response and the percentage of the responders in the audience. Measure your own feelings. Take appropriate action. (‘Only be sad if you’re really funny when you're sad’ - Gaulier)

Again: Notice how people are before the thing, then after the thing. Preferably notice how they are during delivery of the thing. It’s all useful information. When you look remember to see.

Contrast is one of the keystones of comedy

There was one thing, then there was another thing. The clown was running and then he fell down. In the pause or gap there is power - if you leave a gap between two words, your listener's brain makes a new connection and gets an endorphin rush.

A contrast is a little surprise.

Man walks into a bar.

Ow.

It’s also the doorway to another world, in the same way that the set-up and punch above creates a world where a pub turns into an iron bar.

Other random thoughts about rhythm:

Staccato is, in general, funnier than legato

Let’s say it has the comic edge on legato. Although of course legato has its place. One of the key ingredients for comedy is contrast (a nice legato tip toe to scare a fellow clown can be followed up by a sharper shock).

Think music

A good regular rhythm is good as a bassline pulse. Once you have established that then an interrupt (eg a small skillful trip) can trigger a laugh.

Useful if after the small skillful trip there is the immediate immaculate resumption of the first rhythm. That way you are selling a ‘thing’, an event, making an interruption which jogs the primed laughing gear (heart, lungs, eyes) into a laugh. If, in the exercise of the mid-stage trip there is a deceleration, a facial comment or a big reaction after that changes or subtracts the original rhythm, then it is more likely that the audience's brains will go into story-making mode and start (unconsciously) looking for meaning and narrative. Keep them in the habit of laughing.

Bassline pulse having been established, then one can play with syncopation. Good for both surprise and suspense (as well as micro-moments of contrast and surprise). Listen to good jazz.

Also good to remember is that the gaps between notes are part of the music - master the magic of the white space!

About timing

1: what’s the secret of comedy?

2: I don’t/

3: timing.

Seems to me that ’timing’ is a function of attention combined with intuition. Plus a knowledge of the rules. And knowing when a rule should be broken. Awarenesses build up over years of practice and judgments are not made with the language based brain, but through ‘sensing’ and weighing up of a myriad of variables.

There’s the rule and then there’s the breaking of the rule.

Did I hear that from someone or was it me?

Chapter 3

Accept everything

Eddie Izzard, doing the intro to his first ever recorded show, has the audience laughing with heartbeat regularity. He then makes an obscure link, creating a tumbleweed moment.

‘…never make that link again’ (followed by the biggest laugh of the night so far)

Eddie Izzard

Failure is good – comedy is all about ‘things going wrong’.

In comedy, the real failure you can have is failure to acknowledge the failure.

(Well, except for when it’s a really good idea to get on and do something surefire/pick up the energy/install a good rhythm as sleight of hand.

When I teach clown I notice the group seems to relax when I say: ‘You are in the safest place possible. The clown is born with a big pink neon sign over her head: Born To Fail.’ If you make a “mistake”* here, give yourself a big tick. You are on mission!’

* I believe there is a valid time to do air quotes.

Relax relax relax

Practice chi gung, tai chi, something. Learn how to return immediately and elastically to your core, to your Hara. Don’t let adrenaline make you blind and deaf to what’s going on. I have seen people blind and deaf to success as well as failure. Both are equally problematic.

Expect the glitch

In the dance of action and reaction between audience and performer, there may (will) come a glitch. If you are pre-prepared for lack of laughter then you will be less surprised when it happens and ready to employ the techniques that can turn failure into success.

Craft is a toolbox

When there is a malfunction it’s useful to make it a practical rather than an identity problem. Look to the craft ingredient you failed to employ/wonder at the relationship between the variables of craft ingredients.

In NLP they will teach you that 'the result of your communication is the response you get' - everything is information. Interest yourself in how to read the data.

The delay

When a piece of craft has been ignored, you may not lose the laughter immediately. When I teach clown I tell the participants that most of the learning happens when they are in the audience position. I encourage them to notice how they feel as audience when their laughter has been ignored, when they have seen something that the performer has not seen. There is a grace time of good will which very quickly exhausts itself. Or to be more precise, the game changes. It is no longer a dance together into a mystery. The performer has become an indulgent parent.

Play the ball where it lies…

I have seen course participants make a mistake and ignore it … you must, as in golf, play the ball where it lies:

There was no laugh. Acknowledge it. (The only failure you can have in comedy is the failure to aCknowledge the failure)

You did two repetitions to huge laughter, now on the third repetition the laughter is less – you must clock it.

When there is failure

Clock it, have the emotion of the moment: confusion, determined cockiness, doubt, some feeling you cannot name – whatever! so long as it is not hypocritical and so long as you remain aware of the audience and are committing to favour their need over your own.

As I have said elsewhere on this blog, reframe failure. The fear is that 'le bide' is a pit. It's really an opportunity to show your humanity to the audience. It's a play point, a moment. Clown state is elastic. Think of the failure as a trampoline.

Is it Avner the Eccentric who teaches – whatever the response of the audience, have the inner attitude of ‘I know’. A little nod can sometimes release a response from the audience.

Use Cabaret performer/compere Paul Martin’s mantra: ‘Expect nothing, accept everything.’*

Practice equanimity.

Be curious.

Some people want to work the failure to the hilt (this needs a blog post on its own) to work the dying fall really need sound comedy craft and dramaturgical skills to make that longer arc work.

Love the ‘Sad Normals’

‘The clown loves normal people’ - Gaulier

The clown should love the audience not in a lovely-dovey way but as devotedly as Dug the dog in the Pixar film ‘UP’. ‘I will follow that man’.

Even Down-beat or cynical clown needs to attend to the audience’s rhythms in order to play with them. Think of the miserable git personal of Jack Dee and the deliberately-and-knowingly patronizing but secretly audience-aware Stewart Lee. (Stewart Lee loves the audience so much he wants them to be better people).

To balance with the above point:

Self-belief

This is a term we have all had difficulty with in our lives. But the audience really enjoys watching someone who is enjoying themselves. They are lit up, alive. Open, soften breathe, bring in the clown genius. Use it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed